Contents

Song structure is important

Creating a song is more than simply stringing verses and choruses together. We look at song writes and wrongs…

Song structure theory has rules. But you know what they say about rules? Actually, they say lots of things about rules but here are two – rules were made to be broken, and you have to know what the rules are before you can break them. While Judge Dredd may not agree with the first, the second is certainly true and never more so than in writing a song.

Song structure is probably not the first thing you think about when you start writing. You probably work on the verse or chorus, or maybe you have a good riff that you want to expand into a song. So you get that down and then you start to think about the other parts – the intro, how many verses, middle eight, do you want an instrumental, what time signature would be best, the ending…

Some song genres have a fairly rigid format, others are more flexible, and you need to know where you can bend the rules and why you may not want to do so in order to make your song stand out from the others. Let’s look at the sections you’ll find in most songs and the part they play in song construction.

Song Intro

Yes, this leads the listener into the song. It may be two, four or eight bars long or longer. Some songs don’t have any intro at all. A pop song intro will often be reminiscent of the chorus or the hook. In a club song, it’s often a good idea to have eight bars of rhythm to help the DJ to mix match your song. They say that music publishers typically only listen to the first 20 seconds of a song before deciding whether to reject it so if you’re sending material to a publisher, keep the intro short and get into the song as quickly as possible. Save the 5-minute intros for the CD version.

Verse

This is the preamble to the chorus. It sets the scene, certainly lyrically, and as the verses progress they may tell a story or recount episodes from a situation although that’s by no means essential. Verses are typically eight or sixteen bars long and melodically not usually as strong as the chorus although, again, that’s by no means essential. However, it often seems as if the songwriter ran out of ideas when writing the verse. One of the strengths of The Beatles’ songs is that verses and choruses are equally strong and most people could hum or sing their way through most Beatles hits. Not so with many songs where the verses are little more than fillers to get you to the chorus.

Chorus

This is the bit everyone remembers, whistles and sings along to. It should be the strongest part of the song – and generally is – or it contains the hook. It’s usually eight or sixteen bars long.

Middle eight

As a song progresses, there’s a danger of boredom setting in for the listener. The middle eight offers them a break and typically comes after a couple of verses and choruses. Some people think of it as an alternative verse and that’s one way to look at it. It often modulates to a different key or introduces a new chord progression and it usually doesn’t include the song title. However, all too often it’s simply an excuse for waffling on for a few bars. Although it’s called the middle eight it could be four or sixteen bars long.

Bridge

Many people use the terms ‘middle eight’ and ‘bridge’ synonymously and so popular is this usage that it would be churlish to disagree. However, among those who prefer to note the difference, a bridge is a short section used to bridge the gap between verse and chorus. It may only be two or four bars long and it’s often used when the verse and chorus are so different from each other that a ‘joining’ phrase helps bring them together.

Instrumental

This is part of the song without any vocals. Yeah, okay. It’s often an instrumental version of the verse or chorus, it may be an improvised variation on one of these, or it may be an entirely different tune and set of chords altogether. Sometimes it fits into a song where a vocal middle eight would otherwise go.

Breakdown/Break

This term has been high jacked from songs from the early 1900s when it was common either to reduce the instrumentation or stop it altogether while a tap dancer would strut his stuff. The term ‘break’ is still sometimes used to indicate an instrumental section. ‘Breakdown’ is now most commonly used in dance music for the section where the percussion breaks down or is reduced, and it may be the dance equivalent of the middle eight.

Outro/Ending

Once upon a time, songs had definite endings but the mid-1950s heralded in the era of the fade-out and songwriters thought they would never have to write an ending again. However, fade-outs became such clichés – to the extent that fade out meant cop-out! – so songwriters started writing endings again. With that in mind, you can do as you wish, and considering that the endings of most songs get talked over or cut short by radio DJs and mixed over by club DJs, you have only your artistic integrity and your CD listeners to answer to. Some songs work extremely well with fade outs but listen to songs in your chosen genre to see how other writers approach endings. But whatever you do, avoid like the plague the three-time tag ending.

Hook

The hook is not a song part as such; rather it’s the term used to describe the part of the song that people remember and sing. It’s what they buy the record for. It’s usually the chorus although it need not be the entire chorus, but simply a two- or four-bar phrase. It could be an instrumental riff as in Whiter Shade of Pale or Smoke on the Water, or a processed vocal as in Cher’s Believe.

Putting the song structure together

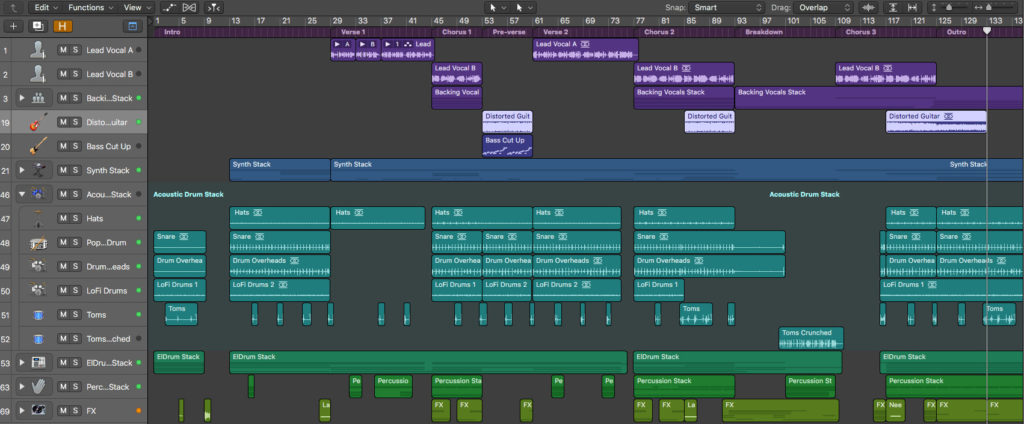

Having described the parts of a song, let’s see how they are commonly arranged. The most popular arrangement by far is simply verse-chorus and repeat. Here are two variations on the theme:

- Intro

- Verse 1

- Chorus

- Verse 2

- Chorus

- Chorus

- Outro

- Intro

- Verse 1

- Verse 2

- Chorus

- Verse 3

- Middle eight

- Chorus

- Chorus

- Outro

You get the picture. However, these are conventions rather than rules so you can adapt, change or ignore them as you see fit. But they have developed for a reason and that is simply to make the song as immediately appealing to the listener as possible.

Song structure examples

Listen to some of the Stock, Aitken and Waterman hits of the 80s (it’s not compulsory if you really can’t bear to) and you’ll see that most follow the simplest format, guaranteed to brainwash the listener with as many repeats of the hook as possible. They tend to be:

Intro (similar to the chorus)

Verse 1

Chorus

Verse 2

Middle eight

Chorus

Chorus

Outro

Notice that the hook’s there straight away in the intro, there’s only one verse before the chorus so you get to it as quickly as possible, and the chorus tends to repeat at the end, just to imprint the hook firmly in your mind.

There are obvious exceptions to these formats. Ambient, trance, chill-out music and the like, are natural candidates. With these, you can start at the beginning and work through to the end creating an evolving music form without any clear verse/chorus structure. Genres such as trance tend to build to a series of crescendos several times throughout the song. However, even these types of songs often have a hook or two on which listeners can hang their hats.

Song build-ups and downs

Bearing in mind that the purpose of a song is to keep the listeners listening and not allow them to get bored, you need variety within the song. Simply strumming a guitar and singing verse/chorus/verse/chorus won’t cut the mustard unless you’re in a folk club. The usual method is to start with a simple arrangement and add to it as the song progresses.

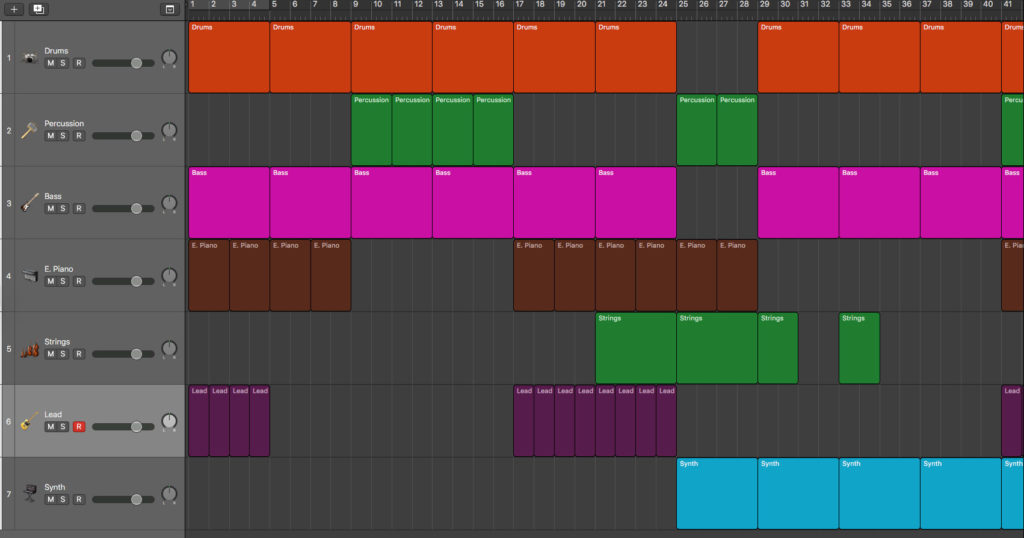

So, the first verse might consist of light drums, bass and rhythm guitar. As you move into the second verse you could add strings or a synth pad. A drum fill takes you into the chorus which would include busier drums, maybe some additional percussion, a fuller string arrangement and perhaps a lead line. When you dip back to the verse, you revert to the simpler arrangement.

The middle eight is usually a lighter arrangement than the chorus and gives you the opportunity to use different instrumentation if you want to. When you hit the second chorus, add backing vocals and a lead riff. The final chorus is the culmination of the song and you can add more backing vocals, more percussion and additional lead lines.

Listen to songs in the style you are writing and analyse their formats to see how far other exponents have stuck to or departed from the traditional formats. when you’re familiar with the rules or conventions that they use, then you can experiment by breaking them.

Song Structure Tech terms

Three-time tag

A popular way of ending songs, particularly when sung live in cabaret, simply consists of repeating the last line three times and then raising the last note an octave.

Drum fill

A roll around the drums, often on tom-toms and typically lasting one or two bars moves a song from one section to another such as from verse to chorus.

Lyrics

Everyone knows that lyrics are the words to a song but while lyrics may also be poetry (although more often than not they aren’t!), poetry does not generally make good lyrics.

Song structure – more info

Wikipedia – a very in-depth look at the technicalities of song structure

Soundscapes – an excellent, if academic, analysis of Beatles songs.

12-Bar Blues format:

http://www.wholenote.com/l467–12-Bar-Blues-What-is-it

Songwriting:

http://www.robinfrederick.com/write.html

Songstuff – a free members site for, er, writing songs

Song Structure – conclusion

Songwriting isn’t black and white. Well unless you’re writing on a piano I guess. In short, these structure formats are incredibly useful but they don’t define the entire world of songwriting. If your song sounds great with an unusual structure, then that’s great! But now that you know the loose ‘rules’ of song structure then you’ll probably start to dissect more of the music you consume. This will hopefully mean that you’ll start to take notice of what works and doesn’t work in your own songwriting. Paying attention to the work of others helps improve your own skills, this is especially true when it comes to song structure.